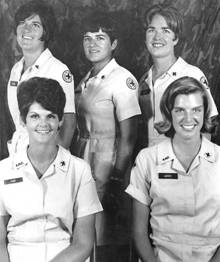

Donut Dolly's Reunon Brings Flood of Memories

|

||||

She was exactly the type of young woman the Red Cross was seeking. Freshly graduated from Whitman College and a woman of the highest moral character (“They wanted the purest and freshest and best women that America could offer.”), committed to obeying the strict rules laid down and brimming with patriotism, she also was unfazed by the very real prospect of peril even as she landed in Vietnam for the first time in April 1969. “We were too naive to think about our own safety,” Driscoll said. “Vietnam veterans have told me, ‘You guys were so brave!’ But we never perceived our danger. We were just oblivious to it, even when we had to dive into bunkers during bombing attacks. We were so young in the ways of the world. This was a chance to see the world and to do something for my country. I was able to experience my generation’s war.” Driscoll and her comrades in morale building were intensely busy. They flew to the top of a mountain, where underneath the Vietcong had dug tunnels. They assisted with the wardrobe of Bob Hope’s big USO show. They always showed up to serve in the chow line and then sat down with the soldiers during lunch. At times they would arrive at 4 a.m. to pass out doughnuts to convoys departing on a combat mission. There was the singing of Christmas songs at fire bases. Everywhere they brought their bags of games and played tricks that made the soldiers laugh, like the photo lighter trick. “We would get on our knees and turn on the lighter with our noses,” Driscoll said, “then we would ask the men to do it. But every man would fall on his face. A woman’s center of gravity is in her hips. Those were funny, funny times.” It was also very funny the time Driscoll came zooming in on a helicopter and encountered 20 naked soldiers below, frolicking on the river. Upon spotting the incoming Donut Dolly, they bashfully started jumping off their air mattresses into the water. It was also fun for Driscoll to experience the country of Vietnam in such a thrilling way, riding in a helicopter above the rice paddies, mountains and canopy of jungle. She often visited three fire bases a day, all of them with very young soldiers yearning to talk to a lovely young woman from the United States. But other times were not fun. Times when Driscoll held the hand of a badly wounded soldier as a helicopter brought him to a hospital. Times when she actually considered the danger, wondering if “Charlie down below was drawing a bead on our helicopter.” Perhaps the worst experience was visiting men in hospitals whom she had met just the week before. This time, though, many soldiers were severely injured. Others had been killed in action. Tragedy always came quickly on the heels of good times and fun. Driscoll was so caught up in her activity of the moment that she had no time to realize that the outside world’s view of America being in Vietnam was undergoing a radical change. When her year of service was complete, the first stop on her journey home was in Australia. What she saw opened her eyes to what was happening. “The Australians were having a big moratorium against the war in Vietnam,” Driscoll said. “Coming from where I had been meeting with all the soldiers, this was a shock. The world was starting to say, ‘This war is not good.’ Being so close to it I wasn’t able to see the war for what it was. My job was to bring a smile to a soldier.” For Driscoll personally, however, this was the richest time of her life. “We wanted to be there. We got instant rewards from our work,” Driscoll said. “The soldiers were always so grateful and kind to us and inviting us to their parties. I only have fond memories of my time there. It launched my life.” Service as a Donut Dolly proved to be perfect preparation for Driscoll’s career as a teacher. “If I was going to be a teacher I had to have self-confidence and the ability to control a situation,” she said. “I was never afraid to get people’s attention.” Driscoll also formed the dearest friendships of her life with her sister Donut Dollies, and that is why she wanted to have the reunion. But she also waned the reunion to be about more than a meeting of old friends. It will bring wide appreciation for the Donut Dollies, just like American soldiers had in 1969.

|

||||

Having Been Led by Love of Country |

|